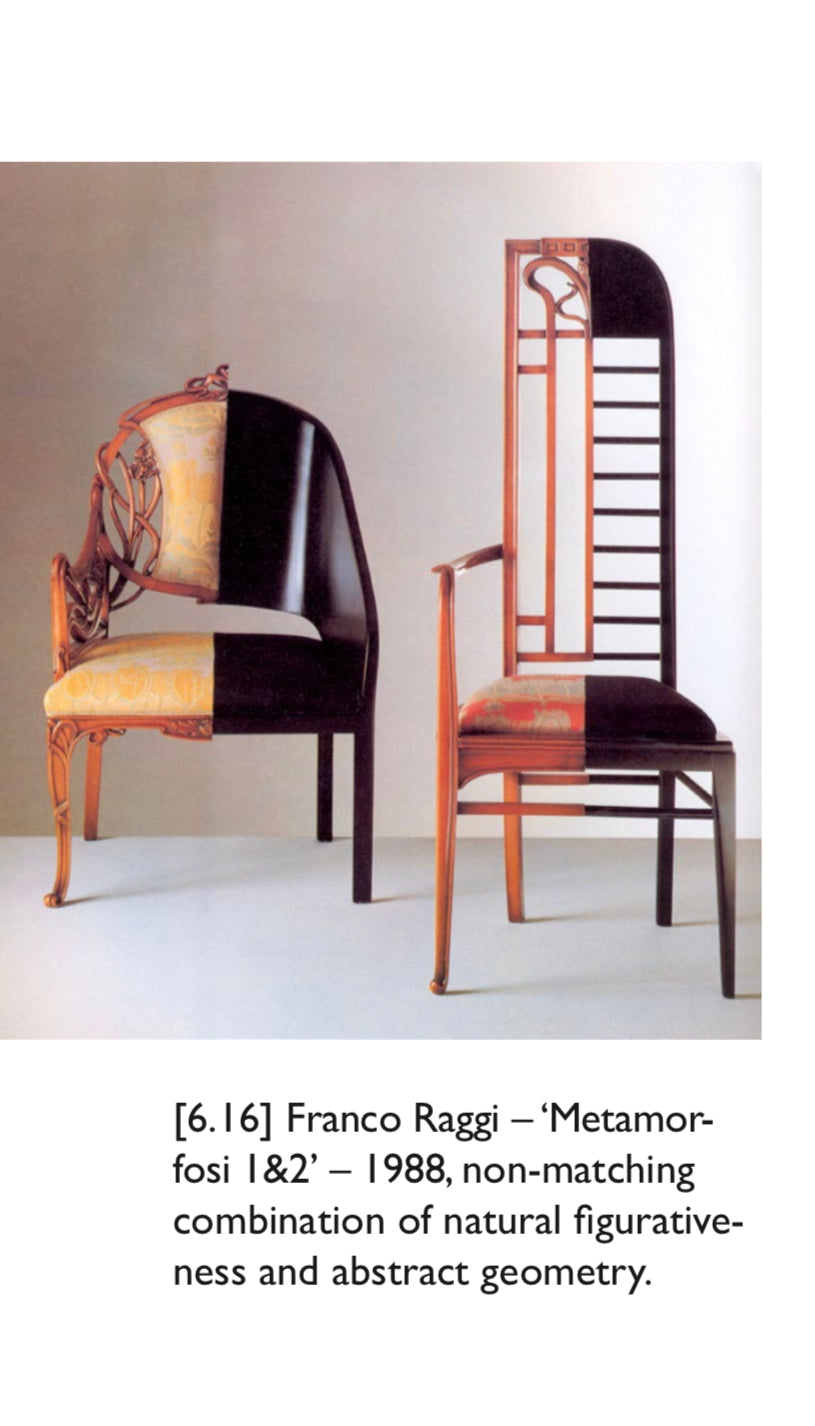

Franco Raggi (B.1945) Metamorfosi Chairs

49 1/2”H x 21”W x 20”D

Seat Height: 19" Seat Depth: 20 1/2”

Arm Height: 27" Arm Depth: 17"

A member of the ByCloudia team will contact you upon purchase to help facilitate shipping.

He has designed architectures, layouts, exhibitions, books, scenery, rooms and articles for famous international design companies. He has a longstanding partnership with FontanaArte, in the early eighties, under the artistic direction of Gae Aulenti, with Daniela Puppa he designed the layouts for events starring the company. Since the late eighties he has created numerous successful projects for FontanaArte: the families Velo (1988-89), Flûte (1999) and Drum (2005).

As an architect he has planned retail areas and showrooms (including FontanaArte), corporate headquarters (including the new Milan offices of Gianfranco Ferré), plus clinics and research centers.

He has taught at the Faculties of Architecture at Pescara University and at the ISIA in Florence. Since 1995 he has coordinated the Department of Architecture at the IED in Milan. In his role as author he has taken part in a large number of exhibitions and held conferences and seminars all over the world.

To understand the designer of the fabulous Metamorfosi chairs, we must go back to the 1970s and the incubation of Global Tools.

Raggi reflects that during 1972, something changed—An intersection between art, architecture and design.

With Italy left in rubble from the war, architects looked for a new way to exist. As the architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable describes, following the Second World War many Italian architects became frustrated at their lack of opportunities to contribute to the necessary rebuilding; a position supported not only by George Nelson, but also by Ettore Sottsass who reflecting in 1976 on his return to Italy following the war refers to, “a land in ruins, and where although there was obviously a need for a lot of building, it soon transpired that it should be done quickly and shoddily, for there was no money.” Thus denied opportunities, architects were increasingly forced into product design to pay the bills; however, the nature of the rapid growth in the Italian economy of the 1960s, and for all the fact that Italy’s so-called “Economic Miracle” was based on exports, meant that much of what was being produced in Italy in the 50s and 60s wasn’t intended for average Italians, but for foreign markets.

Looking for outlets, a group convened in the United States. The Italian artists and architects came together May 26th, 1972 – “Opening of Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. It was the first time at an art exhibition designers from each field joined together in this way instead of being in separate categories or posed against one another. A new era of forward thinking was born.

This led to the creation of Global Tools, which was founded in 1973 by members of the Italian Radical Architecture movement to reconceive the field of architecture and design as a political project through a new form of education. Global Tools called itself a “non-school” and focused on everyday life, aiming to rediscover a direct relationship between craft and design product. Seminars were held as "happenings" and "pre-ecological" operations, promoting the use of "poor" materials and proposing simplifying the design process to counter the early mass-industrial adoption of plastics.

The goal was to promote individual creativity as a form of liberation from the dominant cultural structures and explore the possibility of expressing one's individual creativity within a collective project that shares a common theme and ideas.

The Tools program divided research and work into five themes: communication, body, construction, survival, and theory, which sought to redefine the role of design in the increasingly unstable balance between man and his habitat, the widespread civilization of consumption and the context inside which, and against which, it operated.

With different tools and results, art, architecture and design set forth on this path of “reduction” and reappropriation. Architecture broke free from the modernist and rationalist embrace, which had failed to redesign the environment or society.

Raggi took a particular interest in observing the human body and its relation to function, existence, and object. By redefining the relationship between the body, object and city, this eliminates any mediation, allowing the body to become an instrument of expression, form of language, measure to define and organize the space. Thus the chair, still recognizable in its archetypal form, is modified by losing its functionality and transforming itself from an object into a work of art.

Objects that, by constraining, concealing or subverting the usual relationship of utility, could reveal some- thing else, and by impeding one type of use could unpredictably generate another. objects capable of putting parts of the body or persons into a surprising relationship. objects conceived as utensils for an eccentric anthropology of design. or, more precisely, for a heretical “inverse ergonomics.”

Raggi is always striving to be “radial”, describing it as “something that is not final, or predictable… Not what you are expecting it to be”.

Italian

1988